Bloomberg News

Canada Plots Tariff Retaliation if Trump Starts Trade War

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

Canada is drawing up plans for extensive tariffs against U.S. products if President-elect Donald Trump follows through on his threat to put 25% levies on Canadian goods, according to people familiar with the matter.

The Canadian government’s draft plans for trade retaliation go well beyond the narrow list of U.S.-made items on which it placed counter-tariffs during a 2018 dispute, according to government officials.

Back then, Canada chose to attack certain products, such as Kentucky-made bourbon whiskey, that are exported to Canada from Republican strongholds in the U.S.. The trade spat ended after the U.S., Mexico and Canada came to terms on a revised regional trade deal.

This time, many of those same products would be hit again by Canadian counter-measures, along with items such as orange juice from Florida, where Trump and some Republican officials are based. But Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government is also preparing to go much further if necessary, said the officials, speaking on condition they not be identified.

I’ve got a better deal for President Trump: let’s work together to build Fortress Am-Can and take on the world. When Canada and the U.S. work together as two proud independent countries, we’re unstoppable. pic.twitter.com/DYc809Afvi — Doug Ford (@fordnation) January 8, 2025

One list being circulated internally includes nearly every product the U.S. exports to Canada, said one government official, with the general aim of going “dollar for dollar” on tariffs.

A second official said that in the worst-case scenario — Trump puts tariffs on all Canadian exports to the U.S. — it may not be feasible to fully match the value. But Trudeau's government is examining all options for making it painful on U.S. exporters, the official said.

Government officials emphasized that Canada’s response will depend on what Trump actually does once he takes office. Above all, the Trudeau administration still hopes to avoid a trade war, and has made the case that it’s taking seriously U.S. concerns about border security.

The U.S. president-elect’s news conference on Jan. 7, where he threatened the use of “economic force” against Canada and again suggested the country should be the 51st state, caused a strong reaction in the northern nation and inside the Trudeau government. Trump may not be able to annex Canada, but he can inflict severe damage on a bilateral trading relationship that is worth more than $900 billion in goods and services a year.

In a CNN interview Jan. 9, Trudeau argued that Trump’s annexation talk is meant to turn the focus away from the negative economic consequences of his tariff plan, such as higher consumer prices.

“What I think is happening in this is President Trump, who’s a very skillful negotiator, is getting people to be somewhat distracted by that conversation,” said the prime minister. Trudeau is set to leave office in March after deciding he won’t lead the Liberal Party into the next election.

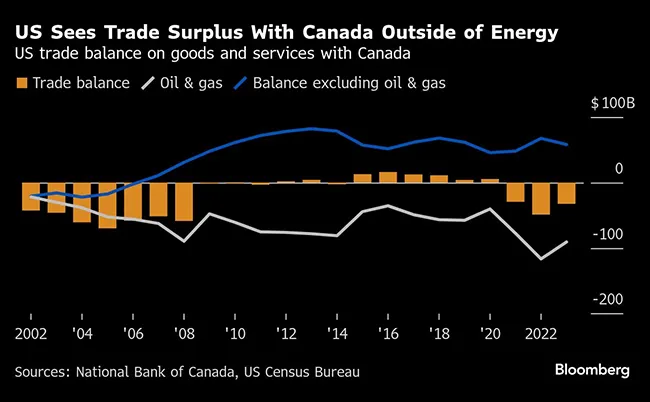

Canada is the world’s largest national buyer of U.S. goods, having imported about $320 billion worth in the first 11 months of last year — slightly less than the European Union, which bought $341 billion. The U.S. trade deficit on goods with Canada was $55 billion during that period of time, according to U.S. Commerce Department data.

Retaliatory tariffs would also punish the Canadian economy, however, pushing up costs for households and businesses while they’re still recovering from an inflation shock.

From front left: Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, Trump and Trudeau after signing the USMCA at the G-20 Leaders' Summit in Buenos Aires in 2018. (Sarah Pabst/Bloomberg News)

Under a 25% tariff by the U.S., Canadian gross domestic product would take a hit of as much as 3.8%, according to calculations by Bank of Nova Scotia economists. If Canada chooses “full retaliation,” that cost rises to as much as 5.6%, though it would take a number of years for that damage to accumulate.

“The GDP hit is higher if we retaliate than if we don’t. Of course, that is a cost that might be worth paying, since retaliation also increases the economic cost in the U.S.,” Trevor Tombe, a University of Calgary economics professor, said by email.

“President Trump has promised tariff policies that protect the American manufacturers and working men and women from the unfair practices of foreign companies and foreign markets,” Brian Hughes, a spokesperson for the Trump transition team, said by email. “As he did in his first term, he will implement economic and trade policies to make life affordable and more prosperous for our nation.”

Trudeau’s aides have debated whether to publicly post a list of potential tariffs ahead of Trump’s inauguration. But there’s still a high level of uncertainty over what Trump is actually prepared to do, so the draft retaliation list may not come out until the president-elect reveals his course of action, officials said.

Another option that has been examined by Trudeau’s government is using export taxes on strategic commodities, such as oil, uranium and potash. This would be an extreme step, but such a move would put immediate pressure on American energy prices.

Canadian officials expect that even if Trump doesn’t go all the way with across-the-board tariffs, he’ll still try to curb Canadian exports in some way. That may include another shot at the metals industry, the cause of the 2018 trade fight.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing above or go here for more info

The American steel lobby’s most recent push for tariffs has been more focused on alleged transshipment of steel through Mexico into the U.S., which the major steelmakers argue is artificially depressing prices and injuring the domestic industry. Canada hasn’t received the same criticism.

But a sticking point among aluminum trade hawks is that Canadian shippers of aluminum into the U.S. — mainly Rio Tinto Plc and Alcoa Corp. — are enjoying the windfall of an extra 10 cents per pound on shipping and logistics charges.

Canada isn’t a major global producer of steel. One of its largest producers, Stelco Holdings, was recently acquired by Cleveland-Cliffs Inc., a U.S. steelmaker with a CEO, Lourenco Goncalves, who’s considered an ally of Trump.