NACFE Report Explores Fleets Fueling With Natural Gas

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

To help fleets make an informed choice on whether to switch to natural gas fuel, the North American Council for Freight Efficiency produced a confidence report l to assist those decision-makers in assessing the major issues to help their fleet’s bottom line.

Titled, “Natural Gas’ Role in Decarbonizing Trucking,” the report aims to help those decision-makers think through the major issues concerning natural gas fuels. This report was written from interviews with subject-matter experts at fleets, OEMs, research groups and industry organizations.

“There are many things to consider with natural gas including benefits such as the desire to use renewable natural gas with its negative carbon intensity, cost and the availability (of sites) to fuel,” said Mike Roeth, executive director of NACFE, “but also challenges including the availability of effective battery-electric trucks and methane leakage in our natural gas delivery system.”

The report guides fleets through the plethora of considerations in deciding on natural gas, which is a complex balancing act for fleet managers. Direct economic benefits may accrue because of a reduced cost of fueling a vehicle as well as potential tax breaks. In some cases, natural gas can reduce a fleet’s carbon footprint by about 15%. In addition, lower carbon emissions can be used to sell services to customers who are environmentally conscious.

Roeth

According to the report, fueling with gas lowers a fleet’s carbon emissions because the fuel contains half the carbon of diesel fuel and generates about two-thirds of the carbon for the amount of energy produced when it’s combusted. However, the advantage that comes from fossil gas can be greatly amplified via the use of renewable natural gas, a virtually identical fuel composed of methane, natural gas’ primary constituent, when recovered from agricultural sources.

Methane is initially 80 times as potent a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide. It can readily be recovered from agricultural sources like dairy farms, requires minimal processing, and functions identically to fossil gas in the engine, according to the report. Burning it in an engine in place of diesel fuel converts the recovered methane to CO2 and water vapor. This makes it “carbon-negative” because otherwise, the methane is released into the atmosphere.

Gage

There is a considerable amount of RNG available, noted Daniel Gage, president of The Transport Project, in the report, stating that, last year, 69% of the natural gas that was dispensed as motor fuel was from a renewable source. “That could be from landfill gas, wastewater, food waste, or renewable natural gas from ag waste,” he explained.

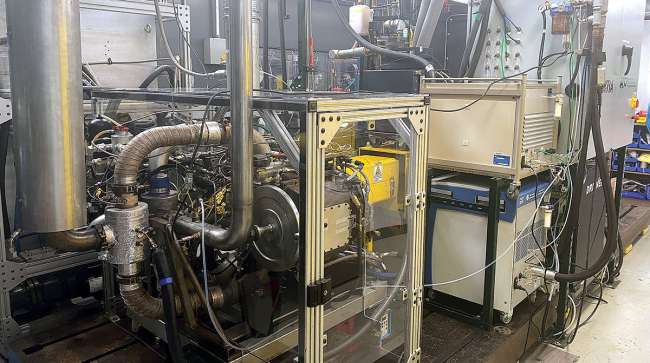

The report is timely because natural gas is plentiful owing to its role in decarbonizing the electric power industry, and because of the availability of Cummins’ new X15N natural gas truck engine. It’s more efficient, and more driver- and maintenance department-friendly than earlier natural gas engines.

There are additional benefits that show up in the maintenance department. Cummins’ new X15 as well as the all spark-ignited natural gas engines already on the road utilize what the company’s David King, product manager for natural and renewable gas engines, describes as a “passive” emissions system similar to that used in passenger cars.

This means a three-way catalyst that kills NOx is used in place of selective catalytic reduction — thus no diesel exhaust fluid to add, and no DEF filters to clean. No diesel particulate filter is necessary either because of natural gas’ lower-carbon chemistry, as well as the spark-ignited combustion system used in spark-ignited natural gas engines. In this type of combustion, the report explains, the fuel and air are fully mixed together before they enter the cylinder, a well-known soot killing technique.

As with any different technology, there are pros and cons. One big disadvantage of natural gas is the size and weight of the fuel tanks. The fuel needs to be highly pressurized for storage, and that means much heavier, thicker metal walls in the tanks. Even under extreme pressure, the energy density of the storage system is much lower. A tank that holds 15 gallons of diesel fuel will take a rig 100 miles. With compressed natural gas, a 58-gallon tank would be required for the same trip.

Jeff Loftus of FMCSA joins TT’s Seth Clevenger to discuss the current outlook on ADAS technology and how it will affect the industry at large. Tune in above or by going to RoadSigns.ttnews.com.

Even with the denser liquefied natural gas, a 26-gallon tank would be needed, and liquefied natural gas has the disadvantage of less availability as well as the possibility of venting if the truck sits for any length of time. The report states that, with CNG, an over-the-road tractor would need both saddle tanks and tanks behind the cab, requiring a 225-inch wheelbase. That means tractor cost will rise $50,000-$70,000 and the resulting rig will be harder to maneuver in tight quarters.

On the other hand, spark-ignited engines are noticeably quieter than diesels, according to King — something likely to help with driver retention. And the Cummins X15N offers diesel-like performance with virtually the same torque as their best fleet diesel — the X15 Efficiency version, while prior natural gas engines lacked the get-up-and-go of diesels. He noted that drivers verify the diesel-like feel and swear equal performance climbing long hills at maximum gross combined weights. Also, at frigid temperatures, a natural gas, spark-ignited engine will start right up — no fuel heating or anti-gel additives needed.

A rendering of Cummins’ EPA- and CARB 2027-compliant HELM X15 diesel engine. (Cummins Inc.)

Natural gas engines are less efficient than diesels on a diesel-equivalent (energy content) basis because of the energy needed to compress the fuel for storage or liquefy it, and spark-ignited gas engines operate at a slightly lower compression ratio — around 12:1 versus 18:1 and up for diesels. However, Westport Fuel Systems Inc. has developed a high-pressure direct-injection fuel system that is within a whisker of diesel efficiency, although not yet widely available in the U.S. HPDI also requires liquefied fuel along with a small amount of diesel fuel for ignition. Volvo is testing the system in Canada.

Although reduced aftertreatment maintenance can save money in the maintenance shop, modifications will be needed there for natural gas. Gas detection systems are required, as well as modifications to shop ventilation, shop furnaces, and lighting systems, and special training in fuel and fuel system handling.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing above or go here for more info

While gas engine lube oil requirements are different, there are quality lubes available that fully meet both diesel and natural gas engine standards, so it won’t be necessary for mixed fleets to stock two engine lubes. Also, while spark plugs had to be changed frequently on earlier gas engines, Cummins’ King says the X15N’s plug changes will align with oil change intervals.

The report includes a plethora of details relating to the risks involved in making the switch to gas, including the possibility that a totally green form of propulsion — whether hydrogen or battery-electric — may become practical even before a fleet has recovered its investment in natural gas tractors and fueling equipment. The report also outlines tax incentives, roughly maps the locations of refueling stations, and verifies that natural gas tractors will not be subject to the cost increases that diesels will face in 2027 as they already meet the tougher NOx standard.

The online NACFE presentation on the conversion to natural gas can be found at this link.