Bloomberg News

US Oil Dominance Hinges on Quiet Corner of New Mexico

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

About 100 miles east of UFO-capital Roswell, a dusty corner of New Mexico with more cattle than people is quietly buttressing the U.S.’s world oil dominance.

After pumping less crude in the years leading up to the pandemic than top counties in neighboring Texas, New Mexico’s Lea County has been rapidly gaining ground. Output there has expanded faster than in any other U.S. county, last year becoming the first to ever produce more than 1 million barrels per day, according to energy research firm Enverus. Neighboring Eddy County will hit the million-barrel-a-day milestone by September next year, predicts energy analytics firm Novi Labs.

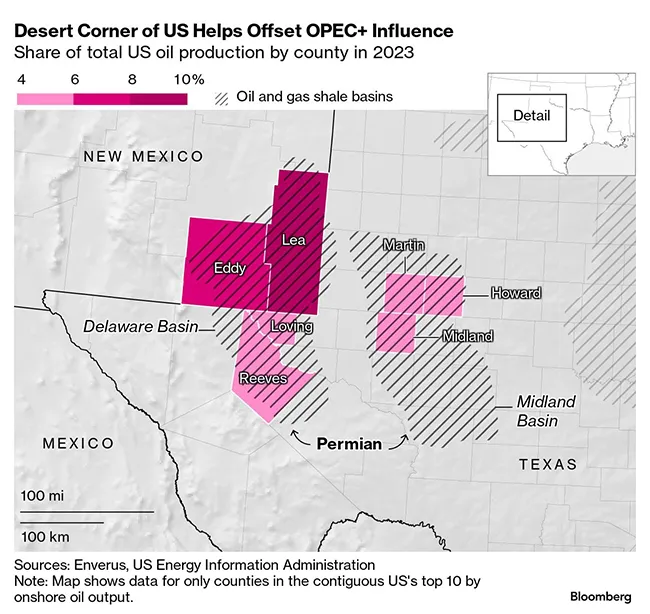

In fact, data shows the two New Mexico counties accounted for 17% of all onshore oil output in the contiguous U.S. last year, and before the next decade, they’re expected to pump more oil than the next five biggest counties combined.

“Since COVID, the Permian Basin has been the only significant source of supply growth,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas energy economist Garrett Golding said at an industry conference in Hobbs, N.M., earlier this summer. “And since Permian growth is centered in New Mexico, technically that means the world oil market depends on what happens in New Mexico.”

When the adoption of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, about 15 years ago made tight deposits of oil and gas readily accessible across the U.S., drillers swarmed to the U.S.’s most prolific basin, the Permian. Straddling parts of Texas and New Mexico, the oil-rich area was generally seen as the U.S.’s best tool to help offset the dominance of Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies, which try to control global oil prices by coordinating crude output.

Originally, much of the U.S. fracking activity was centered around the Midland side of the basin, where an experienced energy workforce plus the appeal of Texas’ famously light regulatory touch attracted wildcatters and Big Oil alike. Texas ranch owners in general offered more sprawling and contiguous acreage leases than in New Mexico, where tracts of land are often smaller and sometimes controlled by state or federal government.

Texas was originally better on the geology front, too. Oil in the Delaware, a sub-basin of the Permian that pushes into New Mexico, is trapped below the surface in more difficult-to-reach formations than in Texas. New Mexico’s stricter drilling and environmental rules didn’t make production as easy, either, operators say.

“Because it was deeper, it was thicker, it was higher pressure, it was harder to overcome that 15 to 20 years ago,” Andrew Parker, senior vice president of geosciences at Matador Resources Co., said of New Mexico.

That preference has since shifted. Although Texas is still flush with oil, it’s being churned out at a slower pace as the Western Hemisphere’s busiest basin ages. In New Mexico, though, there’s still plenty of untapped acreage, with only about one-third of the Delaware Basin already drilled, according to Novi Labs. Much of that land sits atop multiple layers of shale-oil rock, which drillers call “stacked pay.”

Foran

“The Delaware Basin has proven to be the best place to drill because it has 5,000 feet of stacked pay with 25 or so different discrete targets,” Matador CEO Joseph Foran said. “While over there in the Midland, you basically have two formations you really go after with about six targets.”

Improving technology means it’s not as hard to get the New Mexico oil as it once was, and a boom in infrastructure,, including pipelines and gathering stations, has made the Delaware Basin more accessible. For instance, the Dune Express, a 42-mile-long, fully electric conveyor belt system that transports fracking sand between Kermit, Texas, and New Mexico, is expected to come online later this year.

“All the things that made it challenging back in the day are now the things that make it great,” Parker said of the New Mexico side of the Permian. “And they’re the reasons that we prefer this side of the basin to the other side.”

Cox Automotive's Kevin Clark discusses how dynamic parts management can transform your fleet services. Tune in above or by going to RoadSigns.ttnews.com.

Still, the New Mexico side comes with its challenges. For one, drilling in the Delaware is more expensive, with average wells costing about $9.8 million apiece compared to just over $8 million in the Midland area, Enverus data shows. That makes it harder for small companies to keep pace with better-funded oil majors. As costs balloon, an influx of new private equity has elbowed its way into the state.

“Projects that run $10 [million] or $11 million a pop have handicapped the smallest to medium-size legacy producers,” said New Mexico State Rep. Larry Scott, a longtime oil and gas engineer and a Republican. “Guys like me that operated or may still operate 50, 60, 200 well bores vertically are having a hard time competing.”

New Mexico operators must also contend with a stricter regulatory environment than they’re used to in Texas. Flaring, or burning byproduct gas when there’s nowhere to send it, has been mostly banned in New Mexico, meaning drillers need to find another way to get rid of any natural gas. The state also has tougher rules on disposing water, a major component of oil production that has been linked to earthquakes; lawmakers and operators are considering efforts to treat more oil field wastewater for reuse.

Regulations and oil production strike a delicate balance in New Mexico, a state run largely by Democrats at a time when climate change continues to be a big policy issue for the national party. Still, Vice President Kamala Harris hasn’t shared many specifics on her oil and gas stance as the Democratic presidential nominee. During her short-lived 2019 presidential campaign, Harris called for a ban on fracking, but she has since signaled that’s shifted.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing above or go here for more info

Mariel Nanasi, executive director of New Energy Economy, a New Mexico anti-fossil fuel group, says if any big energy state were to consider stopping drilling for environmental reasons, it would be hers. “Why? Because the values of ‘love of land’ are so strong here.”

The biggest challenge to that, she admits, is the billions of dollars the sector brings in every year. “All we need to do is figure out how to get $13 billion, essentially. And if we can figure that out, which I have some ideas about, then we could leave it in the ground.”

Missi Currier, president and CEO of the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association, estimates the sector’s contribution to state coffers every year is even higher — closer to $14 billion, or about 40% of the state’s budget. Currier says she spends a lot of time trying to educate New Mexicans about the industry’s benefits. For instance, due to oil and gas production revenues juicing New Mexico’s revenues, the state was able to be the country’s first to offer free child care and college despite being one of the country’s poorest states.

“If oil and gas stopped in New Mexico,” she said, “within a decade, we would be a Third World country.”