Bottlenecks Wear Down World Economy’s Fleet of Containerships

[Ensure you have all the info you need in these unprecedented times. Subscribe now.]

Container shipping, the backbone of the global trading system, is showing signs of fatigue as the pandemic descends into its darkest days.

Carriers reaping the biggest profits in at least a decade are struggling to operate reliably as bottlenecks worsen around ports from southern England to Shanghai, contorting supply chains for everything from car parts to cosmetics and medical equipment.

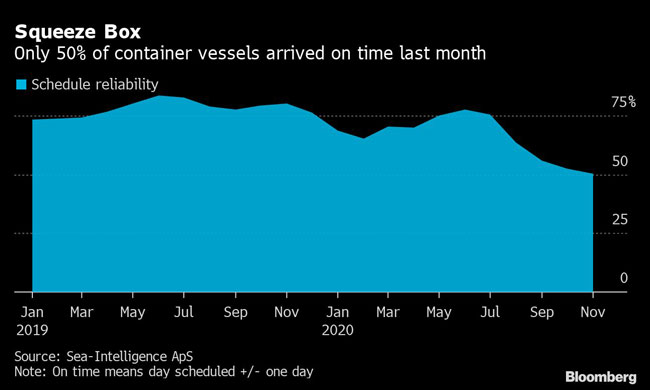

Just 50.1% of container vessels arrived on time in November, down from 80% a year earlier and the lowest level in records dating to 2011, according to a service reliability index compiled by Copenhagen-based Sea-Intelligence. From Asia to North America, on-time arrivals dropped below 30%, less than half the long-run average globally.

Delays can add costs, induce operational headaches and restrain revenue for the shippers of cargo — companies like Costco Wholesale Corp. The Issaquah, Wash.-based chain of 803 warehouse-size stores on four continents expects the situation involving container shortages and late deliveries to persist for a few more months.

“There are instances of 50% or 100% or even more sales increases of an item, and if we could procure more we’d have even higher sales,” said Richard Galanti, Costco’s chief financial officer, on a conference call earlier this month. “We’re managing through it, and expect relief not until March or so of 2021.”

Slowly clogging up since September, the main artery for trade between China and the U.S. is still choked. Anchored off the coast of California over the weekend were almost 20 containerships waiting to offload at Los Angeles and Long Beach, up from about a dozen at the end of November. The Port of L.A. expects to handle 152,000 inbound containers this week — a 94% increase from the same week a year ago.

Weston LaBar, the CEO of the Harbor Trucking Association in Long Beach, last month expected container volume through the L.A. ports would stabilize by mid-February, when Chinese factories typically shut down for Lunar New Year. “Now we’re hearing already about a lot of bookings through June and July,” he said.

Alan Murphy, CEO of analysis and data provider Sea-Intelligence, cautions that the current imbalances in containers are concentrated in North America and says the strength of demand probably won’t be sustained if COVID-19 vaccines enable U.S. consumers to quickly shift spending back to services like travel and hospitality.

The shipping disruptions should calm down in the first half of 2021, Murphy says, but don’t expect the container liners to make their overcapacity mistakes of the past, which included under-bidding in freight rate contracts to below break-even levels.

“The game has changed fundamentally — not because of coronavirus but because of how the carriers responded,” he said, referring to a sharp reduction in sailings in the pandemic’s early months. “They are now capable of tailoring their supply to the available demand at a tactical level that they’ve never been able to do before.”

That’s what worries freight forwarders and other shippers, and the concerns extend beyond the troubles in the Pacific. The European Shippers’ Council, a Brussels-based group representing cargo owners, is crying foul about “degraded services” and surcharges, and wants the European Commission to look into the market dynamics.

The main sticking point: Spot rates to transport goods, which typically fade in the final weeks of the year, are still soaring despite the service disruptions. The rate to ship a container of goods from China to Europe jumped 17% last week, tripling from a year ago to more than $4,400, according to Hong Kong-based Freightos, an online shipping marketplace.

“Of course we want the shipping lines to be healthy,” said Jordi Espin, the council’s policy manager for maritime transport. “However, to make these kinds of profits when we’re in pandemic rescue mode, we don’t think it’s fair.”

RELATED: Federal Maritime Commission Worries About Delays at Ports

Rolf Habben Jansen, CEO of German container line Hapag-Lloyd AG, said in a Bloomberg Television interview on Dec. 22 that he expects freight rates will remain strong at least for the first quarter. While he expected some easing of the market going into the second quarter, he said visibility that far out is low.

Shippers and container liners are always sparring over prices and reliability. But the pandemic has spotlighted the upper hand the liners now have after a decade of consolidating and forming alliances among themselves, said Olaf Merk, head of ports and shipping at the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s International Transport Forum.

“That is something that the competition authorities will have to look at, I think, and some are also doing it now,” Merk said, referring to the U.S. Federal Maritime Commission’s investigation into the carriers’ role in American port congestion. “The situation in which we are now gives a lot of possibilities to the carriers to coordinate capacity and that of course increases the risks for shippers.”

‘Stress Test’

The world’s top container line, Copenhagen-based A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S, this month called the challenges “the most dramatic stress test of the past 75 years.” Other industry representatives say there are multiple reasons on land why the system is straining, like trucker shortages, surging e-commerce purchases or Brexit stockpiling.

Stuffed with 20%-30% more cargo than it’s used to handling, the pipeline is bound to face some snarls.

“Even with this COVID cargo crunch that we’re now in the middle of, things continue to move,” said John Butler, president of the World Shipping Council in Washington, which counts the big liner companies among its members. “When you so significantly overload the system, it doesn’t immediately snap back.”

Butler dismissed the notion that the industry lacks competitiveness, calling it “cutthroat frankly.”

Meanwhile, shares of Maersk, which ranks No. 4 on the Transport Topics Top 50 list of the largest global freight carriers, are flirting with an all-time high. And the industry more broadly banked profits of $5.1 billion in the third quarter, a four-fold increase from a year earlier. With a solid fourth quarter, the cumulative red ink of the past five years will become net profitability, according to figures compiled by John McCown, a container-industry veteran and founder of Blue Alpha Capital.

He said the pandemic gave the container carriers a lesson about how to hold firm on capacity as they shift into a longer-term period of slower demand growth.

“It’s been a major learning experience about having more control over their destiny,” McCown said. “But it’s not been without its struggles.”

RELATED: Congress Eyes Support for Busy Ports

Among the turmoil of 2020: overworked mariners and cyberattacks. But one of the more remarkable events happened on Nov. 30, when the Japanese-flagged ONE Apus hit rough seas sailing from China to the U.S., sending more than 1,800 containers overboard.

The ship and crew returned safely to Kobe, Japan, but the incident probably doused some shipper’s hopes of ending a turbulent year with a bang: 54 containers that plunged into the water were filled with fireworks.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing:

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | More